by Alagi Yorro Jallow.

by Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Fatoumatta: Being black in America already has lots stacked against all black folks, particularly dark-skinned African extraction from Africa migrate to America. You are presumed guilty of many things.

“Black in America” is like a fortress that is all at once forbidding and inviting. As an African arriving in America, I took it for granted that I would gain access to that fortress of black belonging by shared ancestry. How mistaken I was. Melanin identity goes beyond the skin. It courses through our separate histories and through a collective unconscious that causes blacks to reach out across continents. It is wise for indigenous Africans to figure out how to become black politically and economically in America. Socially? Love can find a way.

Fatoumatta: The black American has been actively engaged in emancipation on the African continent since, most notably, Marcus Garvey. In the ’60s through ’90s, Congressional Black Caucus members and TransAfrica Forum (now Trans-Africa) were responsible for fighting the American legislative and corporate anchors that propped up an oppressive white supremacist reign in South Africa.

Pew Research Center statistics estimate indigenous Africans in the U.S. at about two million. This is likely a very conservative number because many African immigrants who have multiplied within the U.S. do not participate in the census. Although a 2019 national New American Economy report notes that “African immigrants boast higher levels of education than the overall U.S. population,” they remain a population that seems utterly uninterested in the incredible possibilities that come with rising like a monolith.

Fatoumatta: The story in these statistics is that African immigrants are not going anywhere, and they will remain recognized as black people within the socioeconomic stratification of American society. Some Africans have fought for African desks in local governments, arguing that socio-culturally and politically, they are unique enough to receive a separate recognition from African Americans. Forming lobbying power as Africans for African interests is fine, but attempting to create distinct honor on the tapestry of black is delusional.

Fatoumatta: Let me share my little experience in America a few years ago. This experiment has a very familiar ring to it. When Africans come to America, we discover that being called “African” is an insult lower than what is called a “nigger”. I recalled watching an interview where Oprah Winfrey, an American talk show host, and media executive said that as a child, other black kids would call darker-skinned kids “African,” and that was the most painful insult ever. I had laughed then, the African that I am, at the absurdity of it, the funny grotesquerie of it, especially knowing I too had been called “African” for an insult– twice, both times by black (African-American) people.

Fatoumatta: I will talk about that awakening another time. It is an awkward conversation between siblings separated by centuries of painful and shame-laden histories that have produced a discomforting identity crisis. Suffice it to say it was an excellent introduction to understanding race issues in America. This is how Africans in America react to their own identity as an insult (caution- stereotypes ahead): I experienced quite well West African migrants fight back loudly and unapologetically. East Africans withdraw into a shell and mind their own business. North Africans camouflage into a Middle-Eastern identity. Southern Africans watch with dull familiarity, and Africans from Central Africans go, Francophone mostly minding their business.

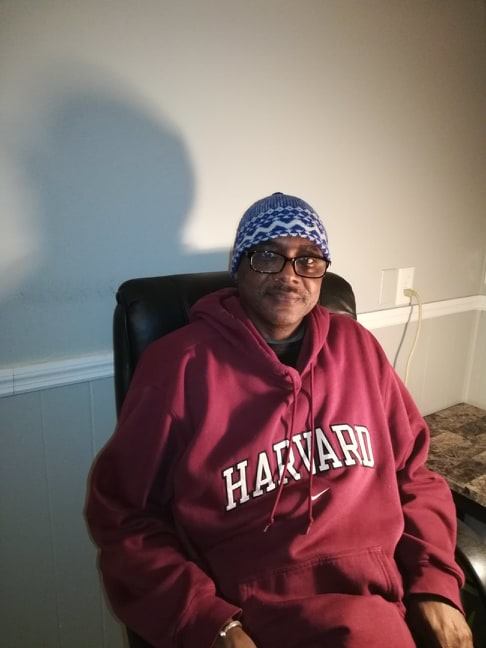

Fatoumatta: When I moved from the Gambia to Washington DC, my reception baffled me: The racist ridicule I got was mostly from the black American people of Native American identity, and my experience with the majority of many Africans in America tell me they have shared the same ordeal of evidence like mine.

I was living with fellow students in the Constitution Avenue North West of the city of Washington DC, then a mix of Asians, whites, Latinos, and some blacks from Ethiopia, while pursuing graduate studies and working as a student in resident fellow at the National Journalism Center.

Fatoumatta: I could see black people who embraced their own self-fashioned African identity with fierce pride. However, one thing seemed clear to me: We African immigrants and our African identity were troublesome for many blacks. I would also come to learn that the black status was equally disturbing for many Africans. It seemed to me we reminded blacks of identity we had been taught to be ashamed of.

In the Gambia, racism was a concept that existed only in books and never in conversation. Tribalism is what we lived with daily. Our identity was and still is ingrained in ethnicity, not in skin color. It explains why most Africans experience being called “black” or “African” for the first time when they come to America. Neither “black” nor “African” are conscious identity markers for Africans in Africa.

Fatoumatta: I began to fit into my African-in-America identity. Washington, D.C. is a slower and more deliberate city than Boston and New York. You get to pause and attempt real human connections. I felt more at home there. In Washington, D.C., I found kindred spirits in the activists and black intellectuals steeped in the smarts and grits of politics and position.

Many primordial Africans in America find little value in identifying with Black hood. We resist being identified with blacks once we become aware of the American caste system that puts melanin-rich humans at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Africans in America have this false hope that being an immigrant saves them from classifying that totem pole. We check the box “Other.” When we make it, most buy homes outside the city, as if American cities and their inner-city component haunt them with a certain stigma of failure.

Fatoumatta: This reticence about bonding with blacks has made indigenous Africans miss out on some of the most amazing inter-personal relationships possible. This claim will undoubtedly be met with derisive laughter by fellow Africans in the U.S. who say we cannot handle the aggression of black people in relationships. Unfortunately, the angry black person is a stereotype, one as dangerous and misinformed as to the ugliest stereotypes about Africans held by black people.

Fatoumatta: I want to share this bitter experience I had in New York years ago. I entered a high street shoe shop that was offering many items on sale. Sale items were on the right—regular items on the left. I had stood by the door watching the rowdiness before finally deciding to go in. During the period, I noticed the white store attendant left white shoppers and directed blacks to the sales area.

As soon as I went in, I walked towards the non-sale area, and he came to me with that silly, fake smile and directed me to the sale area. I ignored him. He then said the sale items were to the right.

So I told him I could read, and asked why he did not say this to the whites who entered and that I noticed he directed just the blacks. He smiled sheepishly and said something like he felt I might be interested in the sale items. I could have kicked his buck teeth in!

Then I reminded the clod again that I could read and identify sales from non-sale items and that if I were interested in the rowdiness of the sale area, I would have gone there. I then thoroughly dressed him down and insisted he was stereotyping. The bosses heard the altercation, and I think he has pulled away from the post and replaced it. In his jaundiced opinion, no black person could afford no sale items. Alternatively, better still, we could not provide anything better than a sale item.

Fatoumatta: One day I was in a drug store (Duane Read now Walgreen), and this black teenage girl walked by me and brushed me. She def was wrong. She then turned angrily and insisted I apologize. Usually, I would have ignored her. Or lectured her. I promptly apologized and walked out of the store. That girl could have called the cops, and I could have been severely manhandled and locked up, especially being a black male.

Fatoumatta: Many years ago, in the same New York, I was window shopping. Suddenly a black cripple in a wheelchair started swearing violently at me. If that “niggger” had a gun, he would have dispatched me. My offense? He insisted I was not window shopping but looking at him! I did not even see him! I called a cab and left the area.

Fatoumatta: Last year the mild climate in summer walking with a cup of coffee and take a long stroll in Michigan the other day I saw a pair of cops saw a black male teenager in a car–a Lexus–with two older white women. They drew their guns, ordered the boy out of the car and down on his knees, handcuffed him, and forced him into their police vehicle. Given what cops with drawn guns often do to black male teenagers, it may be a bit of a miracle that nothing worse happened. Incidentally, the boy was the grandson of one of the two women; the other woman was giving grandmother and grandson a ride home from church—just another day in our post-racial society.

Fatoumatta: The worse ones are the killings and mailings and insults and discriminations against people based on their color. In America. Europe. Asia. South Africa. I even experienced it in Switzerland at the airport and gave it back to the security guy. The world must rise and finally face racism and tribalism and fight it. Individually we must oppose it wherever we encounter it.

Moreover, we must never be racist. Racism is evil. It is a product of inferiority complex, even though those who do it imagine they are superior.

Chronicle: Dilemmas, Challenges and Duality of A Black African from Africa in America

Ma sha Allah great and thanks for sharing