Part II

Alagi Yorro Jallow

Fatoumatta: Facebook can be a place to provide many different political persuasions to be a safe place to express views and exchange thoughts with others. So please keep commenting nevertheless, and continue to debate with spirit…. and civility. This is an unflattering commentary on the social media generation. We have at our fingertips the most incredible engine of knowledge production and dissemination and the most robust aggregation of human intelligence in the history of humanity, and what do we do with it? We use it to traffic ignorance, hate, sleaze, and smut.

Fatoumatta: Facebook can be a place to provide many different political persuasions to be a safe place to express views and exchange thoughts with others. So please keep commenting nevertheless, and continue to debate with spirit…. and civility. This is an unflattering commentary on the social media generation. We have at our fingertips the most incredible engine of knowledge production and dissemination and the most robust aggregation of human intelligence in the history of humanity, and what do we do with it? We use it to traffic ignorance, hate, sleaze, and smut.

This only goes to prove the definitive axiom of this era – the divergence between our moral and material advancement. Technology is a beautiful thing, but its benefits to people can never exceed the limits imposed upon their imagination by their values.

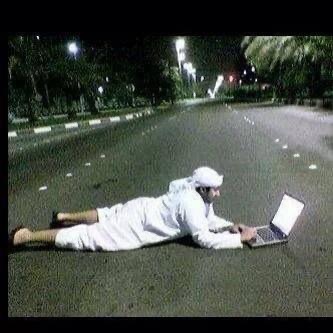

Fatoumatta: If one criticism can be levied against social media, it has made too many of us narcissists and voyeurs. We upload bits of our lives that should remain private, and we feast on the salacious disclosures of celebrity indiscretions, hungrily lapping up their misfortunes, their slices of beef, and their tiffs. The rise of the Kardashians who most pungently exemplify the sordid post-modern trend of being famous for being famous forcefully illustrates the laws of celebrity – there is no such thing as bad publicity, life can and should imitate melodrama, and that an otherwise nondescript existence can be skillful if cynically distilled into soap-operatic set pieces designed to break the internet.

Fatoumatta: Facebook inspires crass and even abusive rhetoric, spurred on by tribal and political groupings. The notion of a village ‘Bantaba’ as a place to hear differing opinions now exists more in the digital space than the physical. However, we see increased polarization and self-selection in our network of friends. The more I read the comments or statues on Facebook, and the more convinced the Gambia is hopeless.

Fatoumatta: The price of fame in a world saturated by ersatz icons and pop culture idols is the willingness to shred the veil of privacy, or in local parlance, the readiness to dance naked in the marketplace and provide grist for Galleh Yadicone’s mill. Thanks to social media, celebrity status for all is a few keystrokes and camera clicks away.

If in previous eras, vanity was the inability to pass by a reflective surface without pausing; today, the inability to live without preening for Facebook, Instagram, or tweeting the minutiae of lives. In a sense, the invasion of privacy has been supplanted by the surrender of privacy. It is the bizarrely schizoid trait of a generation that thirsts for public approval yet wants to retain unquestioned personal autonomy. We want to do as we please but also want to be applauded for doing so. We want to simultaneously enjoy the privilege of unilateral action and the pleasure of universal approbation. In other words, ‘It is my life, but it is your drama, and you must applaud.’

Whether it is an entertainer disclaiming paternity of his children on social media or a couple (and parents) exchanging tit for tat allegations of infidelity online, the cost of winning the applause of a virtual audience is the destruction of authentic relationships with actual people. The things that might have otherwise been repaired, or at the very least, quietly liquidated with the dignity of all parties preserved, are blown to smithereens before the virtual audience with scant thought for the collateral damage – those little ones that have no interest in fame, and will only be left with shame, scarred by the overexposure of family feuds and domestic affairs that should have been dealt with privately. The most appropriate response to the popular culture’s attempt to force-feed us with other people’s garbage is, “No, thanks. This is none of my business.”

Voyeurism makes us disturbingly conversant with the tawdry details of celebrities’ private lives. For many, such knowledge mitigates their existential funk and fills a psychic void. It is also helpful if temporary distraction from massive problems – terrorism, recession, climate change, geopolitics, poverty – and allied tough stuff that we are either unwilling or unable to think critically and constructively about.

Fatoumatta: A celebrity marital meltdown, for example, is far more entertaining fare. At least, however relationally inept we may be, we can pronounce with authority the fragility of a celebrity marriage. Besides, the celebrities themselves were the ones that appointed us judge and jury. We cannot but deliver judgment as judgmentally as we can.

Fatoumatta: The age of reality TV and social media has blurred the lines between real life and theatre, the personal and the public, fame and infamy, and most tellingly, between tragedy and entertainment. Some people genuinely cannot distinguish between these domains. Some years ago, some dear family friends were involved in a fatal car crash. Some onlookers at the scene decided to record fellow human beings perishing in the flaming wreckage rather than try to help. A few even had the temerity to post ghastly videos on Facebook.

The triumph of voyeurism over empathic impulses is something we witness frequently. The brutal lynching of alleged robbers recorded by onlookers with sadistic detachment in all its macabre detail and circulated online. After every criminal atrocity, it has become almost customary to find gory pictures of dismembered corpses, severed limbs, and the like floating on social media. Posters of such material often claim that they intend to shock the viewing public out of its apathy. Like the strategy of” shock value” that fuels the gratuitous pornography of many music videos, this approach also encourages the pornography of violence as posters compete over who can upload the most gruesome pictures. Nothing, it seems, is unacceptable in the pursuit of shock value.

Fatoumatta: Despite their claims to be motivated by humanitarian concerns, the purveyors of such graphic material are themselves merely objectifying the victims of those crimes, doing them further violence posthumously by deploying them as props in their self-gratifying psychodramas aimed at inciting hatred and mass hysteria. The bandits, armed robbers, and killers may be bloodthirsty vampires. However, the morbid and grotesque connoisseurs are necrophilic vultures feeding on the victims’ remains.

Ma sha Allah great and thanks for sharing