Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.

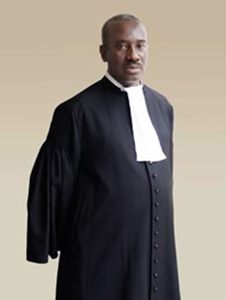

” If the media in this day and age uses their power to attack an ethnic group or racial group, they will have to face justice.” Former Chief Prosecutor of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal For Rwanda (ICTR), Hassan Boubacar Jallow, told the global media following the guilty verdict to jail journalists for Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) for inciting the Rwandan genocide.

Fatoumatta: The trial of Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) journalists was historical in the media fraternity calling attention to what became known as the ” hate media” during the tragic period in the African country’s history. Some of the Gambia’s vernacular, national broadcasting F.M. radio stations and social media network channels, particularly on those social media streaming and WhatsApp network and other platforms on Facebook, are mild versions of the now-defunct Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM). In addition, two Rwandan journalists have been sentenced to life in prison and a third to 35 years for their roles in fuelling the Rwandan 1994 genocide in which 800,000 Tutsis and Hutus were murdered.

Left unchecked, the continued propagation of negative ethnicity and exclusionary ideology by vernacular F.M. stations could ignite the country some time. Radio can directly incite and set an agenda for hate and acceptance of or involvement in violence against “the other.”

Moreover, the sad thing is that such inflammatory broadcasting happens in the full glare of the Communications Authority of the Gambia partly because PURA has no spine to move against and bring the law to bear on wayward owners vernacular F.M. platforms.

Fatoumatta: Journalists use their profession to save the Gambia from impending catastrophe since the media can promote peace and cause civil unrest. For example, the Rwanda genocide, which resulted in the death of over a million people, was triggered off by two local radio stations in that country. Unfortunately, in recent times, all we witness in the nation’s media are misleading headlines, exposing the country to grave danger if not checked. However, media practitioners should ethically use the profession to enhance the bond of unity and the country’s overall development.

In Rwanda, an agenda was set for the Hutu audience of Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), emphasizing that all Tutsis were a threat to all Hutus on a long-term basis; that the only way to protect the Hutu was to destroy the Tutsi; that as Hutu leaders deemed the threat to be immediate and local, you as a Hutu should join the collective effort in exterminating the Tutsi. Thus, the Rwanda genocide was a cascading series of actions deriving from the representation of the Tutsi as the enemy.

On December 3, 2003, the verdict marked the end of a landmark three-year trial. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in Tanzania heard how the media played a significant role in inciting extremists from the Hutu majority to carry out the 100-day slaughter of ethnic Tutsis and politically moderate Hutus. As a result, all three defendants were found guilty of genocide, incitement to commit genocide, and crimes against humanity from the northern Tanzanian city of Arusha.

Fatoumatta: The sentencing of those journalists in Rwanda for their roles in fueling the 1994 hate and genocide in 2003 also marks the beginning of the end of the impunity of hate media practitioners play a significant role through their hate media and ends a critical point of a historic trial that highlighted what became known as the “hate media” during the tragic period in the African country’s history.

The international criminal tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), held in Tanzania, heard how the media played a significant role in inciting extremists from the Hutu majority to carry out the 100-day slaughter of ethnic Tutsis and politically moderate Hutus.

“This tribunal has set an important precedent that says if the media in this day and age uses their power to attack an ethnic group or racial group, they will have to face justice,” the chief prosecutor of the ICTR, Hassan Boubacar Jallow, and current Chief justice of the Gambia and a Director of World Justice Project told the global media after he successfully prosecuted those broadcast journalists propagating hatred, tribalism, and genocide through the use hate media.

Chief Prosecutor of the Rwanda tribunal Hassan B. Jallow said the use of “hate media,” which acted as propaganda outlets, helps explain how ordinary Rwandans – even children and grandparents – were influenced to participate in the killings. In Rwanda, an agenda was set for the Hutu audience of RTLM emphasizing that all Tutsis were a threat to all Hutus on a long-term basis; that the only way to protect the Hutu was to destroy the Tutsi; that as Hutu leaders deemed the threat to be immediate and local, you as a Hutu should join the collective effort in exterminating the Tutsi. Thus, the Rwanda genocide was a cascading series of actions deriving from the representation of the Tutsi as the enemy.

At the trial, several emotional witnesses, including media employees, compared the role of the media to that of fuel on a fire. Phrases like “go to work” and “the graves are not yet full” were read by radio D.J.s during the spring of 1994. A newspaper called on citizens to exterminate the “cockroach Tutsis.”

Ferdinand Nahimana, sentenced to life in jail, was a founding member of Radio Television Libres des Mille Collines (RTLMC), Hassan Ngeze, 42, the owner and editor of the Hutu extremist newspaper, Kangura, who also got life.

“Let whatever is smouldering erupt,” Ngeze wrote in the newspaper days before the genocide.

“It will be necessary then that the masses and their army protect themselves. At such a time, blood will be poured. At such a time, a lot of blood will be poured.”

RTLM, known as Radio Machete, broadcasts the names and addresses of the country’s Tutsi minority and Hutus who sympathized with them.

“Nahimana chose a path of genocide and betrayed the trust placed in him as an intellectual and a leader. He caused the deaths of thousands of civilians without a firearm,” said the presiding judge, Navanethem Pillay.

Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, a top executive at RTLM, who boycotted the trial, was given a 35-year sentence, which was reduced to 27 years for time already served.

Fatoumatta: Their sentences follow the jailing of Belgian reporter Georges Ruggiu three years ago. He was jailed for 12 years in 2000 after pleading guilty to direct and public incitement to commit genocide. In testimony against the three sentenced yesterday, Ruggiu said: “The editorial policy of RTLM was to diabolise the RPF [the Tutsi dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front] and the pro-RPF personalities and to prove that U.N. peacekeepers deployed in the country were biased in favour of the RPF.”

The BBC’s Ally Nugenzi, who worked as a journalist in Rwanda, said that the radio station pinpointed targets during the massacre.

“RTLM acted as if it were giving instructions to the killers. It was giving directions on air as to where people were hiding,” Nugenzi told the BBC’s news website.

The outcome drew comparisons with the 1946 Nuremberg trial of Nazi publisher Julius Streicher, who used films and cartoons to incite hatred of Jews and was executed for his role in the death of 6 million people.

By soaking their journalism in ethnic hatred, the three men turned their media into weapons of war, the court said.

Kangura, which means “wake it up,” published what it called the “Hutu 10 Commandments,” telling people to kill.

Fatoumatta: The Committee to Protect Journalists says that in 2020, 262 journalists worldwide were thrown in prison, and Reporters Without Borders says 90 percent of crimes against journalists go unpunished. Even in democracies that pride themselves on being free, demonization of journalists and allegations of “fake news,” and limitations on the protection of journalistic sources are undermining their work.

As efforts to control speech and information increase, the U.N. Human Rights Office has guided how to distinguish free speech from hate speech through the Rabat Plan of Action, which suggests setting a high threshold for interpreting the restrictions imposed by international human rights law in restricting freedom of expression. Its six-part threshold test takes into account the context, intent, content, extent, speaker’s status, and likelihood that the speech in question would incite action against the target group, and is being used in Tunisia, Côte d’Ivoire and Morocco, and by the European Court of Human Rights in a recent judgment on the Pussy Riot case.

“RTLM broadcasts was a drumbeat calling on listeners to take action against Tutsis,” Judge Pillay said. “RTLM spread petrol throughout the country little by little, so that one day it would be able to set fire to the whole country,” he said.

RTLM ‘HATE RADIO’

RTLM, established in April 1993, became known as “hate radio.” Many of its journalists were accused of preaching ethnic hatred and encouraging Hutus, who make up about 85 percent of the population, to massacre Tutsis. The court heard how from April 1994, RTLM incited the killers, using expressions like “go work,” “go clean,” and “the graves are not yet full.”

Georges Ruggiu, a former RTLM reporter, was jailed for 12 years in 2000 after he pleaded guilty to direct and public incitement to commit genocide. He testified against the three defendants.”The editorial policy of RTLM was to diabolize the RPF (the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front) and pro-RPF personalities and to prove that U.N. peacekeepers deployed in the country were biased in favor of the RPF,” Ruggiu, a Belgian, told the court during the trial.

He said RTLM received information from Hutu Interahamwe militia about operations they planned and “search” notices for people or cars, then broadcast on the radio. The genocide ended when the RPF, advancing from bases in neighboring Uganda, toppled the Hutu-led government. Hundreds of thousands of Hutus, including many Interahamwe, fled into the then Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The U.N. tribunal is keen to show progress in trying former senior officials to counter Rwandan government accusations of inefficiency. The court, set up in November 1994, has now sentenced 16 people, four of whom are appealing against their convictions. More than 40 suspects are in custody.

Fatoumatta: Today in Rwanda, freedom of the Press and information are guaranteed as long as it does not prejudice public order and good morals. While there has been a loosening of control over online media and radio talk shows with limited restrictions – with severe penalties- for journalists who miscalculate the unstated, vague and arbitrary limits on their report.

Human Rights, News, Opinion, Politics

Save The Gambia from the Catastrophe of ‘Hate Media’

Ma sha Allah great and thanks for sharing