Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.Part III

A hundred years from now, people are still going to be talking about President Yahya Jammeh. As a poster child, he recognized that he had become a symbol in which larger social, economic, and political forces were condensed. However, as a person, Yahya Jammeh lived to anticipate creating a commemoration of life.

Behind the tall white walls of the grandiose home belonging to then the youngest-ruling President in sub-Saharan Africa, ostriches, buffalo, camels, and all kinds of livestock roam neatly landscaped lawns vast private complex said to include a crocodile wetland and lake topped with lotus flowers in his native village of Kanilai 118 Km away from Banjul the capital city.

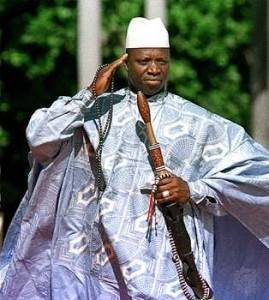

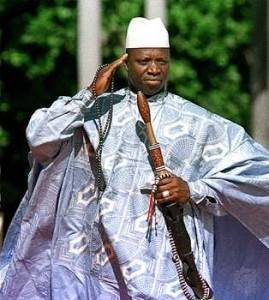

In a poverty-stricken shell of a city outside, where the most miserable pick through garbage for scraps to eat, was a portrait of Shiekh Yahya Jammeh, in long robes, holding a copy of the holy Quran with a sword and prayer beads. The image of a sultan, he is omnipresent—His Excellency Sheikh Professor Doctor Colonel Alhagie Yahya AJJ Jammeh). He gazes solemnly from public building facades, beams proudly from ubiquitous billboards. He is woven into the fabric of countless green shirts worn from the coast of Banjul to the farthest reaches of the forested interior. He is referred to locally as Jilinka or Babilimansa.

He might be young—only 55—but he was more significant than life in The Gambia, the West African nation he has ruled for 22 years in power.

President Yahya Jammeh became the fourth victim of coalition opposition politics in Africa. His defeat has sent a clear message to other sit-tight, royalist leaders across Africa. The long-term solution to the Yahya Jammeh problem should have been to introduce a Constitutional term limit in the 1997 Constitution for the Gambian Presidency to prevent another Jammehism from ruling as he wished to rule for “one billion years.”

When President Yahya Jammeh conceded defeat after the December 1, 2016, presidential elections, the gesture was widely hailed and described as an indication of great hope for democracy in Africa, particularly for the Gambian people, which Yahya Jammeh ruled with an iron-fist for twenty-two years. These 2016 presidential elections were perhaps the most significant political development in Gambia’s political history in fifty-five years. The first alternative transfer of power through the ballot box.

President Adam Barrow is a product of a coalition of opposition parties who provided the platform for change for the people’s yearning. As a result, president Barrow also became the symbol of the people’s hopes and freedom from Yahya Jammer’s dictatorship, the benchmark of brutality, love of witchcraft, and human rights violations.

In many ways referencing the past to bid for editorial prominences, using the past as a context to help explain a news event, and showing how people act in their everyday lives, sometimes theatrical ways that incorporate a sense of past or future; journalism makes itself a vehicle or agent of political memory without the intention of commemorating.

President Yahya Jammeh’s foreign policy interest and public diplomacy were centered on rogue states like Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, and Taiwan, which he embrace compared to his predecessor Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara. For twenty-two years, from July 22, 1994, to December 1, 2016, the Kakistocracy regime of Yahya Jammeh has not succeeded, as promised, in seriously transforming the Gambian economic and social structures in any profound way. On the contrary, poverty and inequality remain high and continue to increase. Yahya Jammeh and his regime often have no comprehensive economic and political visions. Afterward, he styled himself alongside Marxist – Leninist ideology.

When Yahya Jammeh came into power, he became the youngest ruling head of state. At age 29, Yahya Jammeh and his Armed Forces Provisional Ruling Council ( AFPRC) toppled the 30-year-long government of Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara’s People’s Progressive Party (PPP) government and thereby ended one of Africa’s longest-standing multi-party democracies.

The Gambia was viewed (along with Botswana and Mauritius) as an “exception” on an African continent where authoritarianism and military regimes have been the norm. However, apart from the aborted coup of 1981 by the so-called Markism -Lennists Kukoi Samba Sagnia, The Gambia had enjoyed relative peace and stability since it attained independence from Britain in 1965.

Before Jammeh’s rule, The Gambia was known as the “smiling coast,” a place of sunshine, welcome and genuine generosity. It became the home of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights and the headquarters of the African Center for Democracy and Human Rights Studies. It was the bastion of democracy in a continent beset by military takeovers and despotic regimes.

Unfortunately, all of that changed in July 1994, after the coup led by Yahya Jammeh. Most Gambians genuinely fear the 29-year-old autocrat. Nevertheless, there was little opposition to him—many accepted his rule because he has kept his country remarkably peaceful. To do so, he has governed with sustained brutality characteristic of many other dictators.

For over two decades under President Yahya Jammeh and his regime, independent views were considered seditious. The secret police were everywhere, listening for hints of subversion. So Yahya Jammeh name was spoken in whispers unless you were praising him, in which case you genuflected and shouted hoarse at rallies and in religious gatherings, thanking Allah for loving Yahya Jammeh so much as to bless him and his family with a leader of such peerless morality, wisdom, and compassion.

Those who demurred at such scurrilous sycophancy found themselves at the old torture chambers built by the National Intelligence Agency(NIA). The state became a law unto itself, seizing land and property meant for hospitals, schools, and other infrastructure to award to its sycophants. If you sang praises like a parrot — as we were encouraged to do — you were rewarded. Many became overnight millionaires. The country’s economic growth rate went negative.

Under Yahya Jammeh’s rule, The Gambia was in a crisis of morality. It left a culture where wealth, no matter how one gets it, is a redeeming value. However, on the other hand, it bequeathed mind-boggling selfishness, as exemplified in our immoral driving habits; it inculcated a culture of mediocrity and shortcuts; it taught us to see the world through tribalism and to shirk personal responsibility in the execution of public duty.

The sad thing is that Gambians were dealing with a person ( Yahya Jammeh) who was ritualistic and believed in the superstitious practice of ritual killings. It is an open secret that Jammeh, since 1994, has been practicing the ritual slaughter/sacrifice of animals. Mutilated bodies of animals have been found in the gardens of the State House in Banjul several times. A Malian (male) ‘sorcerer’ warned Jammeh to be wary of a woman in his Cabinet wearing a Muslim hijab. The next day, the President sacked his Minister; she was the only one in the Cabinet who wore a Muslim hijab daily.

The Gambia is not the only country that has faced oppressive leadership. In its struggle to stabilize after becoming independent of colonial rule in the 1960s, Africa has suffered its share of “Big Men,” many of whom use fear, patronage, and rigged elections to cling to power. Unfortunately, a few are still around, chiefly in Africa, such as Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni and Cameroon’s Paul Biya, and Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang and Congo Brazzaville Denis Sassou Nguesso.

Like many of the continents’ “Big Men,” Jammeh has displayed plenty of dictatorial tendencies. His government has jailed journalists who dared criticize him personally and has cowed most of the rest into self-censorship. As a result, the Gambia’s prisons are filled with political prisoners, and rivals to the regime disappear or turn up mysteriously dead in the night.

Yahya Jammeh “attacks his opponents by bringing them into his fold, offering them top posts, giving them a piece of the pie,” said a political science professor at Michigan University. “He is like a boa constrictor. He suffocates his prey until it is weak, then swallows it.” A prime example of this phenomenon was Lamin Waa Juwara, Jammeh’s principal opponent, since the coup. He, unfortunately, served Jammeh as Governor and Cabinet Minister. He became a Jammeh party member, and Gambian journalists say he does not speak out much anymore since he joined Yahya Jammeh’s government. “It is belly politics,” the professor said. “If you do not go along, you do not eat.”

The Gambia was faced with many other challenges under President Jammeh’s rule. For example, the country was ranked 168th place among sub-Saharan Africa countries on the UN Human Development Index, which measures literacy, education, and other markers of national well-being. In addition, it puts the Gambia amongst the lowest on the socio-economic development index.

The Gambia during Yahya Jammeh was “neither dictatorship nor democracy, neither paradise nor hell,” said an activist who lived in New York. “We are something in between.”

Jammeh turned civilian after two years of military rule, and polls since then have been marred by allegations of election rigging and corruption. Besides, Parliament—dominated by his supporters—removed presidential term limits from the 1997 Constitution.

The Gambia is considered one of the smallest nations in sub-Saharan Africa. Jammeh has built a vast patronage system, doling out money generously in part through salaries and benefits that come with Cabinet posts. Unlike other West African countries, Gambia has always managed to pay its civil servants and has provided for its government officials every young Gambian’s dream—to be driving a Mercedes Benz or an SUV 4X4 or the American-made Hummer, to be a bureaucrat in a suit, walking air-conditioned halls insulated from the heat and poverty found just outside.

Alhagie Jaye, a Diasporain pro-Jammeh politician, acknowledged that “The Gambia has its problems. There are poor roads, not enough schools, and too much unemployment, but we have to fix things; on our own. Some Gambians regard Jammeh as “the devil they know.” While many would like to see change, they are also afraid things could worsen if he goes.

By contrast, Jammeh has amassed a fortune that makes him one of Africa’s richest men—nobody knows how much he was worth. However, there have been some indications of his vast wealth. For example, media reports have declared that he owned abundant real estate in Morocco and the United States of America, a mansion, and owned many businesses in The Gambia.

In a phrase, Yahya Jammeh and his APRC party left the Gambia, whose value system must be re-engineered to support the prosperous Third Republic. The preceding dictates the kind of President The Gambia needs in Adama Barrow. First, a leader will stake his prestige and sense of accomplishment in achieving the goals set in his campaign. This will mean assembling a team of high achievers irrespective of the tribe or party loyalty, demanding by personal example, total commitment to the task at hand, personal integrity, and innovation.

Second, the country will need to a keenly aware of our despotic past and is, therefore, totally committed to fully implementing the Constitution. This will mean acting, appointing, deciding only based on enhancing the aims of the Constitution. Nelson Mandela understood the human cost of apartheid keenly. Therefore, on the assumption of the presidency, he went about with a single-mindedness of purpose to banish its cultural, institutional, and legal underpinnings completely.

A third Republic of The Gambia will need a leader who can visualize the society anticipated by Constitution and inspire us to see that vision and work towards it. This will mean re-educating us not to analyze our community through a tribe’s prism, thereby creating a new basis for social interaction and political mobilization.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Ma sha Allah great and thanks for sharing