by Alagi Yorro Jallow.

by Alagi Yorro Jallow.

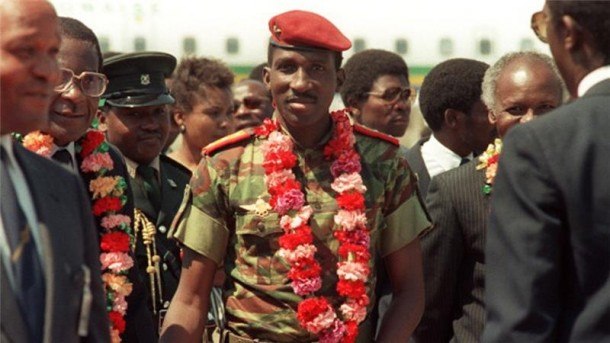

When Sankara came to power, he changed the country’s name from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, “The land of Upright Men.” He stressed Burkinabe culture and pride. During a famous OAU assembly address, in Addis Ababa, July 1987, he made a powerful statement on African self-reliance by proudly showing off his traditional tunic, woven from Burkinabe cotton and sewn by Burkinabe craftsmen.

Until one acknowledges their roots, there can be no real understanding of who they are. Identity is a nagging issue for many African men. Who am I? Where do I belong? Many of us are disconnected from the ethnic origins and cultures of our parents and view ethnic pride as retrogressive. We oscillate between the notion of modern liberal men touting grafted western principles and the old cherished ideals of African manhood as organized by our patriarchal structures. So class identity is often used to fill the gap of tribal disconnect, and patriotism is reduced to a slogan. Only by looking deeply into our past and understanding our history can we evolve new insight to help define ourselves.

Sankara was one of Africa’s youngest leaders at only 33 years old when he seized power in a popular coup. In four years, his contribution to African consciousness was enormous. Sankara was assassinated at the age of 38, but by then, he had lived like a man on borrowed time, and the impact of his life still reverberates throughout the world today.

We keep on waiting for outside forces to intervene in our personal circumstances, yet the solutions to a large part of our problems are within ourselves. We require tenacity to face failure and fear many times over because success is all about getting up one more time like a baby determined to walk. For, if we do not take these calculated risks and stay focused, our lives will be tiny.

Too many men try to keep pace with peer expectations. Manhood is defined by the value of our possessions, and frugal living is associated with poverty. Our consumer culture has sanitized greed by creating a heightened sense of lack. This thinking motivates unchecked consumption for the better part of our lives as willing prisoners of addiction or envy, never knowing the peace of mind that contentment offers.

Sankara was different. He did not amass wealth or create a cult of personality around him. His life was marked by frugality. At the time of his death, he was earning a salary of $450 a month; he did not own much in terms of personal possessions. The most prized item was a car and 4 motorbikes.

It is easy to shout in a crowd. But to hold a different opinion that goes against the sanctioned grain takes courage. To stay true to your conviction until your vision comes to fruition requires perseverance.

Sankara’s achievements on the battlefront and his personal charisma earned him the popular support required to become president of Burkina Faso. But he was soon to realize that not everyone wanted change. The petty intellectual bourgeoisie had interests to protect in cahoots with foreign powers, and they hit back, but Sankara’s commitment to change rooted in solid personal values was unshakeable. In the end, he paid for his values with his life, but his legacy lived on.

Sankara understood women’s place in Africa’s empowerment long before gender activism came into vogue. He was not reactionary, and he realized that the disempowerment of women was linked to male economic dominance by other men who lashed out to compensate for their inadequacies. He started a campaign to restore the dignity of women and return them to their rightful place in society. He studied the roots of patriarchal dominance, tracing it to the advent of private property where women were consigned to a man’s possessions. During Sankara’s reign, several women were appointed to government positions, and his most potent gesture was the day of solidarity with women. On that day, roles were reversed, and men walked a day in women’s shoes, going to the market and taking care of household chores.

Too often, men blame their state of emasculation on the advancement of women. Male disempowerment in Africa can be traced back to the slave trade and colonialism. The effects of centuries of degradation are real. The disempowerment plays out as violence towards women and children, delinquent habits, and recklessness. But with awareness, change is possible. African men must be more proactive in creating safer communities for women and children. It starts with self-examination to determine the triggers behind our insecurities and why we overreact when our position is threatened as the first step towards healing and self-empowerment.

Sankara was a perfect example of servant leadership. The symbols of opulence all but disappeared under his watch. His down-to-earth attitude was baffling. He got rid of the presidential fleet of Mercedes and opted for the boxy fuel efficient Renault 5. He refused to use the air conditioning in his office because he did not feel he earned the privilege. These small gestures were necessary for fiscal discipline. Burkina Faso was one of Africa’s poorest nations, and he understood the injustice of the one percent living off the fat of the land while the great masses wallowed in poverty. Sankara’s brand of leadership was about elevating the collective through organizing and example, which he used as a reflection of his individual worth.

I read somewhere that leadership is the ability to motivate and inspire others to take affirmative and sustainable action. This principle is not pegged to the number of followers. It can just as easily apply to a household or a relationship. The underlying objective is not merely to lead, but how well we lead that counts. At the most basic level, a true leader must live by example. All talk and no action won’t cut it.

Thomas Sankara decreed that his portrait should not be displayed all over the country in official buildings, as is the norm in Africa. He saw no need to develop a cult of personality around him. Despite his high station, he identified with commoners. He was secure enough in his position to be humble.

Success can be overwhelming. It takes a steady hand to ride the waves without sinking into the depths of self-delusion. No matter how great the accomplishment, one must not get too attached to the noise it generates. Sooner or later, the hype will pass, and it is essential to remember the man you were before success came knocking.

Sankara’s style was pragmatic. He preferred tailored military fatigues drawing inspiration from Fidel Castro and like Che’ he wore a beret. He loved motorcycles and dressed appropriately for the bike. He promoted Burkinabe traditional as an expression of belonging.

Style essentially is about knowing who you are and how to express your individuality. It is also about comfort in your own skin. Fashion fades. Do not be a slave to trends, or you will end with suitcases of clothes you detest.

Sankara’s commitment to personal fitness was total. He was regularly seen jogging unaccompanied in the streets of Ouagadougou, so it’s no surprise that he was never overweight. He initiated fitness programs around the country and always seemed energized.

These days as soon as the man makes a little money, it is reflected on his waistline. The more prosperous one gets, the bigger the belly grows. By the time fortune descends, he will have arrived at full-term pregnancy. Physical fitness is not a priority and all about vanity with the advent of short surgical cuts. But an unhealthy lifestyle is expensive because the medical cover is not getting cheaper. Most of the ailments plaguing society are attributed to careless lifestyle choices and are preventable. The human body was not designed to be sedentary, so get off your butt and make exercise a regular activity.